In spring 2018, undergraduate English majors in ENGL 245, “Writing Rivers,” had the privilege of working with the Kickapoo Valley Reserve (KVR) to engage deeply with the past, present, and future of the Kickapoo River Valley. KVR is an 8,600-acre tract of public land located in southwestern Wisconsin managed by a Board of local residents in coordination with the State of Wisconsin and the Ho-Chunk Nation. The KVR Board is responsible for tending to its mission: to protect, preserve, and enhance reserve land so that its unique environmental, scenic, and cultural features provide opportunities for the use and enjoyment of visitors. But it is KVR’s origin story that is maybe most fascinating for the purposes of our class.

In the 1960s, the United States Army Corps of Engineers began using the right of eminent domain to clear landowners—on the land now that now forms the Reserve—to acquire land for the construction of the La Farge Dam. Despite heated opinions on both sides, more than a hundred families being forced off their land, and partial completion of the project, the project was abandoned in 1975 due to environmental concerns and higher-than-expected costs. In the nearly twenty years of local deliberation that followed, it was determined that the land should be converted for public use. The site today is home to the Kickapoo Valley Reserve, though the almost century-long debacle surrounding the La Farge Dam remains controversial in the hearts and minds of many in Wisconsin’s Driftless region.

The abandoned La Farge Dam project, the heated opinions on all sides, the ecological impacts of the project, the resulting Kickapoo Valley Reserve, and the ways the project has lived on—or not—in the hearts and minds of official Wisconsin history mark it as an ideal, local case for learning about and engaging with rhetoric, public memory, and environmental justice.

Students in “Writing Rivers” were challenged to engage these themes through creative and scholarly projects as the culmination of their work in the class.

——————————————————————————————————————————

Pencil on paper, Claire Evanoff (click for detail)

——————————————————————————————————————————

Photos and quotes from former Kickapoo Valley residents, Aberdeen Leary (click for detail)

——————————————————————————————————————————

Caroline Maahs reminds us:

Chemical fertilizers which are used on farms in the basin also result in some nitrogen and phosphorus pollution. . . At current rates of erosion and sedimentation, La Farge Lake would also trap an estimate 100 acre-feet of silt. (Final Environmental Statement 1972, Pg. 29)

Where the cliffs would be completely inundated, their aesthetic value and the plants which occupy the faces, crevices, and overhangs would be unavoidably lost. . . Some of the cliffs which now support various unique plants and plant communities would be inundated, partly or periodically. (Final Environmental Statement 1972, Pg. 38)

And asks:

How would the painting have changed if the water was taken from the proposed La Farge Lake rather than the Kickapoo Valley Reserve?

Would the paper have eventually torn due to excess silt buildup in the water?

Would the paint have reacted differently due to the chemical imbalance of nitrogen and phosphorus pollution that was proposed?

Watercolors with Kickapoo River water, Caroline Maahs (click for detail)

——————————————————————————————————————————

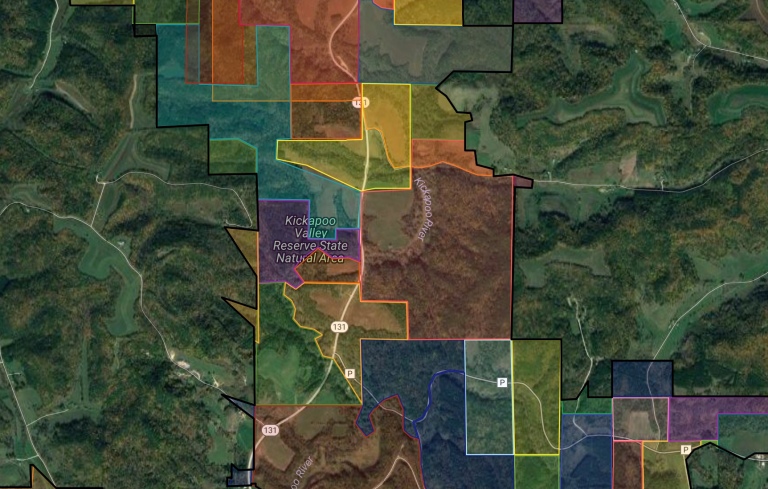

Land History of the Kickapoo Valley Reserve, interactive map, Dagny Mochalski

——————————————————————————————————————————

The Tower almost blends

with April branches,

I receive unsatisfactory

glimpses of the 110-foot

mass as the bus cuts

through rolling hills,

and I ask myself

Why keep the tower?

It seems like a disturbance,

a gray and brown concrete

block amid prairie, plants, and hills.

The tower is an island,

distant and unreachable.

All natural pathways blocked,

building unkempt, faded

and weathered in squares

and rectangles, isolated

by an army of jagged rocks,

obstructed by tangled thicket,

symmetrical, man-made,

out of place.

The tower is what happened.

The valley peaceful, until

the tower invades

demanding

attention,

conflict,

remembrance.

Piper Brown-Kingsley

Power of a Plant

Lavenders, zinnias, irises, and violets,

purple like the northern monkshood clutching

battered banks of the Kickapoo river, existence

uncertain, endangered. This shy plant stopped

bulldozers by peeking between rocks,

prevented a lake from swallowing the valley,

but it was not alone, drooping sedges, arctic primroses,

and cliff cudweeds clung to the Kickapoo cliffs,

their only home. What is the value of a plant?

Could you identify the monkshood? Appreciate mysterious

hoods gracing green stems? Would you look into the rimmed

eye of the primrose? Feel the scratch of the sedge

against unprotected ankles? Conquer muddy ridges to run

calloused fingers along the cudweed’s woolen leaves?

Would you pick these plants? Alive only in the valley.

over frequent floods and vivacious visitors?

Piper Brown-Kingsley

Eminent Domain

Settlers began staking claims in the 1830s,

the brochure said. Slowly the area grew,

attracting people: fur traders, loggers,

until agriculture took over, but the

river wanted to drown

the inhabitants. Destroying

crops, people, houses, towns,

costing millions. Soon the dam

solution flooded the town:

first a small project, quickly spiraling

into a recreational facility,

the new storm of the valley.

Forcing people out of their homes,

tearing apart the landscape,

costing millions, and this time

they couldn’t rebuild.

The government pressed

the Ho-Chunk to sell more land,

the brochure said.They had resided

in the valley for 12,000 years

until Friendship treaties leached

away their land. The Ho-Chunk

were told they had 8 years before

they must leave the Kickapoo,

after 8 months they were exiled

to Iowa. Some stayed in the new land,

hedged between hostile tribes,

others returned to the Kickapoo.

All had to rebuild their lives.

Piper Brown-Kingsley

——————————————————————————————————————————

ILTIS V. PROXMIRE

by Peter M Curry

Character List

Professor Hugh Iltis – Czechoslovakian Botany professor at UW Madison

Senator Proxmire – Democratic Senator, Wisconsin

Senator Gaylord Nelson – Founder of Earth Day, Democratic Senator, Wisconsin

The action takes place in 1970. There is a fundraising event for the University of Wisconsin Institute of Environmental Studies. For some reason both Senator Proxmire and Gaylord Nelson are at this event. Botany professor Hugh Iltis is also in attendance. There has been controversy lately about the long proposed La Farge dam in the Kickapoo Valley Reserve.

There is a long buffet table against the back of the room. The carpet and furniture have been tarnished by overly aggressive event goers in the past. The event has a sort of uncomfortable air as if people are more concerned with the charcuterie boards that fundraising.

Proxmire enters.

Proxmire busies himself with a coupe glass at the buffet.

Iltis enter.

Iltis approaches Proxmire without reservation.

Proxmire: You again?

Iltis: Why do you wanna build that dam? That damn, dumb, dam?

Proxmire: Ok Professor.

Iltis: You and the Army Corps of Engineers. I swear you slogan is ‘keep busy.’

Proxmire: It’ll do a lot of good for a lot of people.

Iltis: Listen Senator. There is Aconite up there… Norther Monk’s Wood! Why do you want to destroy such a rare beau—

Proxmire: The plants grows on cliffs doesn’t it? I would think some it would be fine.

Iltis: No. No, not so Senator. Look… do you know how rare that area is? Outside of the flowers I mean.

Proxmire: Do you care about people’s homes?

Iltis: Don’t strawman this.

Proxmire: It’s going to prevent flooding for a lot of people whose property gets washed away every—

Iltis: THEN MOVE THE HOUSES! For God’s Sake Senator, why insist you build houses in area that is fundamentally stupid to build a house on.

Proxmire: Hey there. These are good people who want to stay where they’ve been living for many years, where they raised their kids for Christ’s sake.

Iltis: I swear, these religious people can’t even take a lesson from the bible. Its raining for however many days and everything is get washed away. Where does the Arc come in? Get out of there. Or is that story a bit too silly? Move the houses.

Proxmire: Look. This thing is gonna create jobs and make a hell of a profit.

Iltis: Those summer cabins on the edge of this thing won’t enrich the economy as much as you think.

Proxmire: I need to have a word with somone over there.

Iltis: Right.

Proxmire exits.

Governor Nelson enters.

Nelson: Thanks for the letter Hugh.

Iltis: Yeah well… a colleague of mine found the Northern Monk’s Wood I was telling you about. Near the Kickapoo.

Nelson: The only Wisconsin endemic?

Iltis: No, Aconite. Common in the Rocky Mountains and up in Canada, but rare here. It can only grow in cold wet places like where we were.

Nelson: Where?

Iltis: Laudermill’s Bluff, outside of Sauk City.

Nelson: How did he know to go there?

Iltis: Well he is from Harvard, Dr. Facet. And these people from Harvard… they don’t make any mistakes, I mean, it’s just one of those things. They are committed to doing anything as long as they let you know they got the degree from Harvard.

Nelson: Did you take some of it? The plants?

Iltis: No. You can’t pick it because the population is so small in Wisconsin. That’s why I wrote you the letter.

Nelson: I’m doing what I can about the reserve.

Iltis: I was in L.A. a few weeks ago and it was Earth Day and, did you know? I found out there it was Lenin’s birthday and so everyone that we went around and were speaking to were saying there were these somewhat tinted environmentalists. Pinkos.

Nelson: Everybody has to have a birthday one day, we just happened to pick the wrong day.

Iltis: I mean it could have been my aunt Millie’s birthday, hers is the twentieth of August.

Nelson: Exactly what I thought.

Iltis: I need to bother you with one more thing. Part of what I’m planning for the Senate announcement, but you need to oppose the dam. It’s the brain child of a blindly technological Corps of Army Engineers. It would destroy one of the finest environmental areas in Wisconsin. It’s expensive and short-sighted. As a conservationist, you cannot, must not support this dam.

Nelson: Well I don’t Hugh. Its Bill who is supporting it at the moment. Maybe if you bother him more he’ll give it up. I think he’s on the precipice.

Iltis: Really? He came out for the dam… thinking he was Sir Galahad on a white horse.

Proxmire enters.

Iltis: Listen Senator. I am concerned even if you build the dam that won’t screw it up like the Army Corps did in New Orleans.

Proxmire: Look we’ve got—

Iltis: They build the absolutely, incredibly stupid levies that have no concrete inside. They are just piles of gravel. What do they expect?

Proxmire: Listen, I never thought I would see my own funeral on the news. Do you think I haven’t given this enough thought?

Iltis: I think you need to go up there and look at those flowers.

Nelson: I am not sure mother nature wants a lake up there, Bill.

Iltis: Yeah, she’s got better things to do.

Proxmire: Look I understand all that. The work they are doing up there is already good. They are getting rid of over mature trees, those forests were supposed to be white pine and white spruce.

Iltis: How do you know?

Proxmire: Well there are a huge number of dead and over mature trees that are falling over or not being used.

Iltis: You need old growth, Senator. The humus is important to build up. Animals and plants, Senator, leave them be so they can deal with the ecosystem.

Proxmire: I’m out of my area of expertise here.

Iltis: That is exactly the point! You want to manage more land in Wisconsin which has so much already. This is one of the few unmanaged areas.

Nelson: Especially unmanaged when you consider its been relatively left alone from glaciers even.

Iltis: Senator… to think that these flowers have travelled so far and are so rare, yet we don’t have the patience to leave them be and enjoy them, frankly, breaks my heart, and to think that the people making decisions, don’t know anything… remotely… they know nothing about this area. It’s insane.

Proxmire: Professor, I was elected to help good people. Many people in the Kickapoo want this dam, they are good God fearing people, who simply want to add something special to their lives.

Iltis: I think this is one of the biggest problems. If you’re religious, just accept the fact that God made that wood and that humanity was just an afterthought anyway.

Nelson: What do people at the University think?

Iltis: The University itself can’t take a position. They have to be very careful. That’s why I need to be an extra loud mouthpiece. I’m going to keep publishing stuff about this, in the Sierra Club.

Proxmire: You’re a fine environmentalist wasting all that paper.

Iltis: How many people’s hands have you shaken today?

Proxmire: A lot.

Iltis: You’ve probably introduced yourself to everyone in Wisconsin.

Proxmire: At no cost.

Nelson: That’s your campaign advertising?

Proxmire: I don’t spend anything on my campaigns.

Iltis: Am I getting the Golden Fleece Award this year?

Proxmire: Depends.

Nelson: You are for the dam though… it’s expensive.

Iltis: Anyway, the lake you want is going to be pea soup in a few years.

Proxmire: Pea soup?

Iltis: Soup from sediments. Do you have the authority to ruin a place that the ice age didn’t even cleave flat?

Nelson: Think about it Bill. About what makes sense here.

Iltis: I imagine a world where you were buried in flowers instead of hauled in a coffin behind a manure spreader. You could make that happen in more ways than one.

Nelson: For the sake of savings, Bill.

Proxmire: Sold. Now I’ve really got to go.

Iltis: Think about it!

Proxmire exit.

Iltis and Nelson get two drinks and sip them.

Iltis: Did I ever tell you my theory about alcohol and the domestication of corn.

Nelson shakes his head.

THE END

——————————————————————————————————————————

People of the Kickapoo, multimedia art, by Erin Goukas

——————————————————————————————————————————

History of the Kickapoo Valley Reserve, rap, by Erica Howe

——————————————————————————————————————————

“UW-Madison students sense ‘hostility’ about Monterey Dam issue,” article in the Janesville Gazette, featuring Nelson Yang and Alexa Johnson

——————————————————————————————————————————

01/07/1975 – La Farge, WI by Will Skalecki

Snow falls gently

like ashes

to rest

on hard Earth

And a flame burns

from the effigy

of a famous senator

What began as a small rebellion

Now – a crowd – beside his coffin

Some with tear-stained eyes

Others, look on with contempt

and some are just there

They stand sheathed in leather and wool

to lament the loss of a summer place

They stand aside

to honor him

But look, the procession has begun

The leaders and the rest

ascend, cursing

at frozen bones

To the top of the tower

where few can stand

and the wind roars louder,

shaking the pines behind the crowd

Last words are whispered

All watch in anticipation

This act of defiance

The greatest, but not the last

The body is hurled over the edge

And snow

like ashes

falls gently

on Earth

to rest

——————————————————————————————————————————

La Farge by Zhiyun Zhao

Based on the People Remember project’s interviews

CHARACTERS

BYRON LAWRENCE

JOYCE STEINMETZ

BRIAN TURNER

PAUL JACOBSON

BRAD STEINMETZ

OLIVE NELSON

ARLAN JOHNSON

BERNICE SCHROEDER

ARNOLD HAGEN

MARY BUFTON

GERALD ERWIN

HOMER MUNSON

BUD MELVIN

MR. WIRTZ

NARRATOR

INTERVIEWER

SETTING

An empty room

TIME

Late 2000 and early 2001

SCENE 1 REMINISCENCE

NARRATOR

La Farge is a village located along the Kickapoo River in Vernon County, Wisconsin. In 1960s, Congress authorized the Army Corps of Engineers to build a flood control dam at La Farge. However, the project was eventually halted in the 1970s because of environmental issues. In late 2000 and early 2001, Bradley Steinmetz, a La Farge High school history teacher, and his students conducted over 50 interviews for the People Remember Project, hoping to record how the La Farge dam project impacted the residents’ lives. The following play you’ll see is edited from their interviews:

BYRON LAWRENCE

The Kickapoo Valley is home.

This is where my people are, my friends are that I grew up with. We had 130 acres, and it was kind of a rough little farm. We milked about 27 cows. Decent living. Farm prices never was real great anyway. But we made a living. And, I don’t know how to describe it, but it was really a good time. And to say the communities, there was a day when you knew everybody. I can remember dad and I and my younger brother was buzz sawing wood. And here comes Ben Kregel walking down across the meadow there. You could almost throw a stone to his house. He jumped right in and helped us. So that was the type of neighbors that was around at the time.

JOYCE STEINMETZ

La Farge is where I grew up.

Although there was different families, we all seemed to be as a group because — and I think part of that was because — the little church there. It was a rural church. The school was there, what they called a one-room school, which was run by the community itself. And I think that’s a reason why our community got to be so close. And we had excellent teachers — and creative teachers, they had to be creative because they had to teach the art, they had to teach the music.

I truly think that I couldn’t have grown up any place, any better, in the whole world (Laughs) than right there. And one of my reasons for that, is because it was the community that I felt was a family.

BRIAN TURNER

Christmas time was really a big deal down there. Always had a Christmas program in the Community Hall and my Dad always went. Got the Christmas tree in, had a big Christmas tree in there and then they decorated with popcorn, balls, and paper, chains and all that kind of stuff. And then they put on a Christmas program. We always got a tangerine, hard candy and peanuts. Every kid got something. There was always gift. Old hall was just a great gathering place, that was really a loss to the community when they didn’t have that hall.

PAUL JACOBSON

Coon Valley is my hometown. I can remember coming to La Farge in 1970, it was still pretty much a stable, non-mobile community. There weren’t a lot of new people coming in every year, or a lot of people leaving.

BRAD STEINMETZ

I would like to go back to memories that I have from my childhood in regards to the floods. That’s one of the things that I remember a lot — from being a kid here in La Farge — there was always floods.

OLIVE NELSON

On the left of us over there, at James Danies’ property, one time the water came right down the valley. It didn’t bother out property that time but there was two times we had floods right through the garage. Of course you know the neighbors were right there to help us clean up the mud and everything.

ARLAN JOHNSON

My children used to get out of bed in the morning and get up, and they were ankle-deep in water in the basement. Bedrooms were in the basement. So yeah, we’ve seen quite a few floods.

BERNICE SCHROEDER

I spent all my life in the Kickapoo area, just a few miles from La Farge.

I’ll start with the Kickapoo region itself, it is unique and quiet and attracts many people. And those of us who spent our life there have such a fondness for that area. The hills are for me personally the big attraction. Those hills are very very old; they were here before the glaciers came. At first the Indians were here. The hills were all covered with forest. And the Indians lived here. During the mid-1800s, they were forced from this land as the white man came in. The white man came in because of the forest, and logging and lumbering was important at that time. The white men, came in and cut the trees, that left the hillsides bare. So when the rain or snow melted it would cause floods. And we had several major floods. They usually classify those and say “Uh the river just goes out of its banks by itself”, “It’s just high water”. And we had major floods in 1912, in 1917, in 1935, and that’s a number we want to remember because the flood of ’35 was the beginning of the La Farge dam.

SCENE 2 CONTROVERSY

NARRATOR

Because of the major flooding in the Kickapoo Valley, the Congress authorized the Army Corps of Engineers to build a flood control dam at La Farge in 1962.

INTERVIEWER

How did you first hear about the project? How did this first happen?

ARNOLD HAGEN

Oh it was years and years before they first started talking about the dam,

before I bought the farm, you know. But no one ever thought they’d do anything about it.

INTERVIEWER

When they were talking about the dam was there any other alternatives to the big dam?

ARNOLD HAGEN

Well, sure, a lot of them said they could put little dams up in all the valleys. Because basically it was flood control that they were after. But when they once got the dam, I think the start for the dam wasn’t supposed to be near as big as it was toward the end. So it got to be a lot of recreation along with it instead of just flood control.

BRAD STEINMETZ

This must have been ‘58, ‘59, something like that. And Governor Gaylord Nelson came to La Farge to speak to the community about getting a dam. For flood control. the flooding really was bad. It was just a total nuisance and farmers lost crops and people got washed out of their homes — pretty standard kind of a thing that went on there. And then I remember, in 1962, when they passed the dam project. I can remember the local paper — the La Farge Enterprise — had a huge headline that the dam project had passed. And I thought, wow that’s really neat. At the time it was just going to be a dam with a small lake, probably have some better fishing and things like that.

And of course then they studied it, and I can remember when they came back with the new plans. I was in college at that time — ‘66, ‘67, they were doing that. And they were going to have this huge lake, and it was going to have all kinds of recreation and fishing and swimming and beaches and marinas. And we were going to be like another Wisconsin Dells. And I thought that was great. There wasn’t a lot going on the valley and people needed jobs and I just thought that would be alright — not really thinking about people who were going to lose their farms and homes and that type of thing.

I became a, (pause) a big dam proponent.

INTERVIEWER

What were your feelings?

MARY BUFTON

Oh my feelings! Um, at first I think we were just little bit excited because it was something different, something to happen. It seemed like this might be a nice thing, to have a lake down the road. But when we thought like that, we weren’t thinking about the people that lived down the road either. Because I think this is a farm that every farm viewed from their own perspective, and everyone was different. Some looked forward to it, and some of them were afraid they would have to move.

ARNOLD HAGEN

Of course I wasn’t for it at all, to start with. I don’t think any of the farmers would have wanted it.

GERALD ERWIN

My family was essentially against it I personally was. I know my brother tried to stall them off as long as he could. He did not want to sell because my people had been there for some generations and we really loved the land although we starved pretty successfully on it. But that was the feeling within the family.

INTERVIEWER

Were most people in favor of the dam project?

GERALD ERWIN

I think most were in favor of it as it was projected and as they hoped for. I think they looked for a financial boom and a big recreational area.

NARRATOR

The Army Corps of Engineer initially planned to acquire 400-800 acres of land in 1962. However, because of the additional plan for the recreational and economic purpose, in 1969, they ended up purchasing over 9,000 acres, a total of 149 pieces of land.

INTERVIEWER

So how did the corps engineers approach you at first to buy your land?

BERNICE SCHROEDER

There had been some publicity on it, and when they got ready to start purchasing the land, I suppose that was about ’67 or 8 that they started buying up the land. They simply came to your door and told you their purpose, that your property was being taken under the law. Our property would be appraised, and if we weren’t happy with that, well, we could go to court.

GERALD ERWIN

Well, I think it was pretty much a matter of compliance. Not much of a choice.

ARNOLD HAGEN

And you didn’t have any choice. Either you agreed with what they said or they’ll condemn it.

INTERVIEWER

Did you feel like, the people who were telling you what you had to do, did you feel like they were approachable, like you could negotiate with them, like you and your fellow landowners had some rights?

MARY BUFTON

Individually yes, I think those people felt sorry for us. Some of them. And I remember thinking in the back down in La Farge with the negotiator and the lawyer, and my husband Rex and I, when we signed the papers, Rex decided there was no point in arguing. You see, really because we couldn’t fight, you know.

BRIAN TURNER

A lot of people didn’t know how to fight it.

I don’t mean to come across like people were backwards, but they were laid back. They didn’t want it to happen. Mom and dad went and got a lawyer. They spent about $10,000 to fight them and they’ve been one of the few went got a lawyer. People just more or less, especially some of these older people. They come in and these real estate agents would tell them, we’re the federal government to take it. Their exact words were they would make them two offers and third time they condemn them. Most of those people were scared to death, so they just take it.

INTERVIEWER

The two offers. Does that mean if they refuse the first offer —

BRIAN TURNER

They come back with the same price.

INTERVIEWER

Oh, they come back with the same price.

BRIAN TURNER

I know they pretty much started out with my dad at the price that he offered. That was our final offer.

INTERVIWER

Did they pay fair?

GERALD ERWIN

I don’t know. I suppose it was market value. I wasn’t in any position to drive a hard bargain. I sort of went along with it.

ARNOLD HAGEN

It’s so disgusting when someone comes around and tells you you’re going to lose your home. They had to put a value on them. They’re supposed to buy at a fair market value. I suppose it probably was. But how do you put a market value on your home?

INTERVIEWER

What happened to your family after they purchased the land?

JOYCE STEINMETZ

Mom said Brad had laughed right out loud when Bradley interviewed my mother — Olive Nelson. She said they gave you two months to get off after the total purchase was completed, and they didn’t get off in time. So they were there an extra two months getting things moved. And they charged them rent those two months [laughing]. Bradley said, ‘you paid rent on your own property?’ and she said ‘yes we did’ [laughing].

INTERVIEWER

What about the other people in the community?

JOYCE STEINMETZ

Some went to Viroqua to live and some moved into town and they just kind of all went different directions, which was kind of sad. Because they lost that contact they had as a community. They weren’t too happy about that either.

BERNICE SCHROEDER

There was a story of this grandfather. When the bulldozers came in to level his barn and tobacco shed, buildings that he had constructed with his own hands, he stood there watching them. He came back to see if there had been some little thing he missed that he would pick up from these empty buildings, and he stood there with the tears running down his face as he watched the bulldozers bulldoze those buildings.

BRIAN TURNER

When the house burned, I remembered my dad leaned up against the tractor in tears and he looked at me and he said, “Life doesn’t begin at 40”. He was just trying to be 40 years old and when the house burned. He was fighting with the Corp and he lost his house and his barn and dad just gave up. They are still here, but he gave up.

INTERVIEWER

We have had people on this project who have said that they simply could not talk to us because they still felt so strongly about it.

BERNICE SCHROEDER

So I suppose you wonder, “Why did these people, the local people, the former land-owners, feel so strongly about leaving their farm, their property?” I guess to understand that, you need to understand the farmer and his land, how the farmer is bonded to the land. He works the land day and night, season after season. He becomes very much a part of the land. It’s almost a spiritual experience with him and his property, the land that he’s on.

SCENE 3 OUTSIDERS

NARRATOR

In 1970s, the Sierra Club, a grassroots environmental organization, started to file suits on environmental concerns, hoping to stop the project. A UW study also shows that the dam might cause severe water quality problems for lake.

HOMER MUNSON

Well you know, the environmentalists got involved, when it was, far along.

I don’t know why they didn’t get involved at the beginning but they didn’t. But that was the reason it was stopped. Um, the quality of the lake would be bad. But I still think it could be built and should be built.

ARLAN JOHNSON

The Sierra Club was one of several factors that brought call for halt to the project.

They were the big pushers of the Arctic primrose. The arctic primrose is very rare to Wisconsin. Take the name alone, it’s called the Arctic primrose. It grows in the Arctic. It’s like a dandelion up there. Dinosaurs are very rare here too. We can always find little things that are endangered, and mess up a lot of good, constructive projects of all various types, not just dams and reservoirs but highways and buildings. Whatever!

INTERVIEWER

So what are your feeling about the Sierra Club?

ARLAN JOHNSON

Sierra Club had no business in here. This was a local issue. They had business in their thinking, but they should not have equal weight with the locals. Don’t forget, this project was for flood control, number one, recreation, number two. They could give a damn about flood con-control. They didn’t care who was flooded out.

BERNICE SCHROEDER

The Sierra Club particularly, and the John Deere chapter of that, located in Madison and they’re beginning objections to building a dam on the river. The theory was they wanted to save the Kickapoo. The whole thing became political. Up until that time, all the state and the federal agencies had favored this project. All our elected officials had favored it. But particularly the Sierra Club who has the power and has the money and has the influence, they went with political, route and forced our elected representatives to change their position.

ARLAN JOHNSON

The whole thing started politically and the whole thing wound up politically. That’s a shame.

The only politician that we had with us was Congressman Thompson and he was a very strong backer of this project. But he was a member of the House, and the other two senators were anti-reservoir project. So we didn’t have a whole lotta chance there.

We had Gaylord Nelson who was a senator, who was the first governor to authorize this project. But then he turned around because he was a champion of saving the world and the environment. So he had no choice. He had to be against it. And then we had Governor Lucey who was against it.

We had Senator Bill Proxmire, who was the chairman of the Appropriations Committee, that’s where the money came. He hung in there as long as he could.

BRAD STEINMETZ

It was a Saturday and Senator William Proxmire called for a meeting at the firehouse here in town.

BRAD STEINMETZ

And it seemed like it was 10 o’clock in the morning and there were several hundred people there — it was just jammed — to see what he was going to say, because he said that there would be an announcement about the project. And of course, Senator Proxmire is extremely important at this time because he was the last of the key elected officials who were still supporting completion of the dam. And when he came into town that day, he basically said he was withdrawing his support of the dam because it had become too expensive, and that there was no way of justifying the amount of money that was going to be spent for the project and the benefits that we were going to get out of it — the recreation benefits were probably going to be somewhat limited because of water quality and things like that. But I don’t think environmentally he was overly concerned about it as much as he was kind of a fiscal watchdog in the U.S. Senate at that time.

ARLEN JOHNSON

I think that was fairly big of him. He had enough guts to come out here to La Farge — made a special trip — and we had a meeting.

BRAD STEINMETZ

He was booed, he was hissed, he was vilified. When people asked him ‘what were we to do for flood protection?’, he said that the government offered low-cost flood insurance, which didn’t give you any kind of flood protection because if you owned a house or buildings in the flood plain, they wouldn’t give you the insurance anyways. That was his way of saying ‘that’s how you can help yourself.’

ARNOLD HAGEN

We found a bunch of dirty stinking politicians that’s what it amounts to. They bought that land to build the La Farge Dam and Reservoir. But they didn’t use it for that, no. To me that just wasn’t right. That’s what they bought it for.

INTERVIEWER

Would it have been okay if they would’ve used it for that?

ARNOLD HAGEN

Sure but you don’t get that when you get a bunch of politicians mixed in it.

OLIVE NELSON

That was the saddest time of our life, the saddest time in our life. We had the dam and then the dam didn’t get built. It was caused by dirty politics. No one will ever know what it’s like until they have to go through it, to have to give up your home.

BERNICE SCHROEDER

The government came in and promised, and my feeling is that when you promise something you follow through no matter what. I felt the bitterness for my neighbors and friends and the people of the valley and how they had been treated. I felt strongly that the government had betrayed us.

PAUL JACOBSON

Everything else aside, I think that was the one thing that people felt really betrayed about because they gave it up with a specific kind of purpose in mind.

My sense from the people was that they would’ve been perfectly content to live there. When they were giving it up, they weren’t giving it up for any real personal gain that they were going to get. I think they gave it up as a gain for the whole, and I think that the biggest disappointment that people gave up land for the project is that they felt that they were doing it for everyone, and specifically everyone in the valley that would benefit from having this lake project and that what they received in it might be of value.

BRAD STEINMETZ

Well you’re probably wanting to hear about the funeral. The funeral that was held for Proxmire. The funeral — Proxy’s funeral, as it was called — was organized by local citizens and held on a wintry Saturday. I remember the snow was blowing and it was kind of cold. And the funeral started out with the services downtown, and Proxmire’s effigy body was placed in the manure spreader. That was the hearse. And they had a couple of mules pulling the hearse. Oh they had music and a sermon and everything.

ARLAN JOHNSON

I remember one time the band leader here at school was very upset, Mr. Pendelton. He had to run the band through the parade twice. They opened up the parade and had to come all the way around and through at the end of the parade.

It was a way of letting off steam — so frustrated.

BRAD STEINMETZ

And then they took the effigy up to the dam and twirled it around in the manure spreader and then threw it down over the dam. And I always thought that that was simply a good example of frustration that the people in La Farge.

SCENE 4: REBUILD

NARRATOR

After a decade-long debate on the future of the Kickapoo Valley, the government decided to give the 1,200 acres of land back to Ho-Chunk Nation, and found the Kickapoo Valley Reserve, under the management of the Kickapoo Reserve Management Board. The Board is controlled by local people.

INTERVIEWER

Some of the land was given to the Ho-Chunk Nation, did you think that was right that the Indians received some land?

HOMER MUNSON

Yes, I think so. After all there was a gradual war. People moved West and scarred of the Indians. And the casino at Baraboo—I always get Bosco and Baraboo mixed up but I think I said that right— it’s just beautiful. And it’s a good thing that white men didn’t kill off all the Indians because white men wouldn’t know how to make something so beautiful as that. [laughter] But I suppose the white men made it anyway, mostly.

BUD MELVIN

Hm, I don’t think that’s right. They had that same opportunity to homestead or claim land as everybody else did. So I think that if they wanted that land, they could have claimed it, they didn’t have to wait ‘till the government bought it and then claim it. I knew most of those people up there that owned that land that the Indians are claimin’. And they literally sweat blood for that land. You know how hard it is to pay taxes and keep a piece of property. I don’t think that’s just because the government bought it, you know, more or less forced them off the land, then they should turn around and just give it away. I mean, with the casinos and everything like that, they’ve got so much money, the Indians, so much money. If they want it why then, buy it! Don’t just give it to ‘em!

INTERVIEWER

Do you think that what they’re doing with the land right now is good? The Reserve?

MARY BUFTON

I think it’s very good. I think this is the happy ending to a mistake.

When we sold and there was going to be a lake down the road and my brother-in-law came over said you know this is going to be worth something some day. In a way, that prophesy is true. What’s left here now is valuable because of the project what’s going to be done with the recreation, the Center, with the beauty of the land. The fact you can step outside and hear a cougar. This type of thing makes it more exciting country than it used to be. There’s some good tings about that. They must continue. They must not stop again.

INTERVIEWER

What do you think of the reserve?

ARNOLD HAGEN

That’s a lot of money thrown away for nothing. It really is.

INTERVIEWER

What do you think should be done with the land?

ARNOLD HAGEN

Oh, I don’t know. They could’ve given it back to us to start with.

BRAD STEINMETZ

Some of the people are against the reserve.

BRAD STEINMETZ

And I don’t think they’re really against the reserve or the concept of what the reserve is. I think they’re still mad about the former project. I think they’re still mad about having their land taken away, and not having the dam and not having the lake. So that’s just a carryover.

INTERVIEWER

So what do you foresee as the future for this area?

MR. WIRTZ

There was this error in the core coming in and the purchasing of the land and relocating of the people and the moving in. But the frustration that I feel is that the rage that I think that comes about from the project that costed many taxed dollars, the effect it has had on many of the people. Not only the immediate but over the course of time. And will continue to affect the people as like tax dollars being put into the area, population, the potential for growth – I don’t see it happening. But at this point more should be done when it comes to developing, and I think people just need to be willing to do what has to be done, as long as it contributes to the making of a good clean rich community, not only for us but for us that have children and families that are growing up.

ARLAN JOHNSON

Transportation has always been a problem here. I think we can see a little prosperity if number one, we get a highway going north.

We could also see some jobs—you gotta have jobs created here, we send young people to school and we get them all brilliant like you are, and then what are you gonna do? Hey, I’m packing out of town. Years ago they all went to Janesville. Why? So they could build cars. That’s where the work was. Why can’t we keep them here? We can. Not all of them, we don’t want all of them here, but we keep a lot of them here.

BRAD STEINMETZ

Well I guess the last thing I would like to say is that, when you look at this dam project, you have to understand that our government is not perfect. Somebody has said that it’s not perfect but it’s a lot better than any others. But this, La Farge Dam Project, and the way the government dealt with people, is a great example of how government should not work. It just was a fiasco all the way through. And a lot of people were hurt, and it set this community back a long ways. And in many respects, here in 2000, 2001, the community is just starting to deal with moving on.

THE END.